Yet again I strike gold in my search for interesting women to interview. Having an affinity for spirituality, foreign cultures, travel and adventures I came across yet another incredible woman, a true academic, an explorer from ‘darkest Peru’, an adventuress and a true ‘Mummy style’ investigator. With her background in the military, academia, and Peruvian spirituality Joan Parisi Wilcox is an exciting cocktail of the intellectual, socially ground breaking and deeply mystical. She is answering my questions in another of my interviews portraying daring, adventurous and awe-inspiring women.

Machu Picchu

As I speak to her she is calm and friendly but most of all kind and generous with her knowledge and her time. I am amazed at the richness of her knowledge and her precision. She seems tireless in clarifying details about the meaning of the spiritual concepts of the Andes. As I listen to her I feel honored to learn this knowledge she is sharing. Her answers are long and detailed. I decide I will present it in her style, just as she would, not changing anything and reporting everything. And here it is.

Joan, thank you for agreeing to talk to us. Where are you right now in the US?

I am originally from Massachusetts and have lived a lot of places in the United States, but am currently settled in North Carolina.

I would like to ask you first about your professional background. I believe you are a writer, an academic, Andean tradition teacher, but you also have a military background? Would you like first to expand a bit on that?

Yes, I served in the US Air Force for four years, not long after the Vietnam War. I was the first woman or one of the first women admitted into the career field I chose, which was Aircrew Life Support Systems. Basically, I worked with nearly two hundred fighter pilots and their gear and training, from conventional gear like communications to anti-gravity suits to the survival kits that were in the base of the ejection seats in the planes.

Joan at work in the US Air Force

WOW ! That is so interesting. Was it difficult being the only woman working with all these men?

It wasn’t easy being the only woman among so many men, including the twenty or so men in my shop doing the same work I was doing. My first commander did everything in his power to make my life miserable! But thankfully he was soon reassigned and my new commander was supportive in every way. I had some adventures in the military, including taking a flight in an F4 Phantom jet and going to water survival school. It all feels like ten lifetimes ago!

Joan with her Andean teacher

BW: How did you become an academic?

After that, I went to university to complete my undergraduate and graduate degrees. I completed doctoral coursework in modern American and British fiction and poetry, with the intent of becoming a professor of modern literature, but I left the program after completing coursework but without that degree. I had become disillusioned with academia. In the years after, I worked as a freelance book editor and as a writer in such diverse environments as a branding and marketing company and the Museum of Science in Boston.

In the mid 2000s, I worked for six years with a group of what I call “frontier” scientists, academics who essentially had to leave the traditional university or laboratory worlds to strike out on their own to explore at the frontiers of complementary health, biology, consciousness, physics, and other realms of inquiry.

BW: Your work still feels very academic even when you teach. There is so much knowledge there.

I have retained an academic approach in much of what I do, meaning I do my own research, ask questions and seek out answers, and verify those answers from multiple sources. There’s a lot of misinformation out there, especially on the Internet, and I like to try to determine what’s reliable and what’s not. I read widely in diverse areas and spend time synthesizing knowledge from different areas, seeking fundamental similarities that could hint at universal “truths.” Or at the very least foster insights I wouldn’t get if I confined my reading to one or two subject areas.

When I began studying the Andean sacred arts that academic approach eventually came into play. I have tried not only to be a practitioner of the Andean mystical tradition but a scholar of the tradition.

I have studied and practiced in many different mystical or shamanic traditions, but the Andean practice, to me, is the most direct, simple, efficient, and effective way to grow, evolve, and engage life in a deeper and more meaningful way.

Ausangate

BW: Have the academic and spiritual paths you have followed clashed?

No. In fact, they complement each other. My areas of interest are diverse, but the primary constellation of interests are consciousness, mysticism, and the nature of knowing and of being. I have also read widely in the sciences, and I have come to see mysticism as its own kind of science. The conventional scientific method involves asking a question (forming a hypothesis), conducting research or doing tests to answer your question, and then, once you have affirmed your hypothesis, having others repeat the experiment to provide independent verification of your results. Mystics the world over, throughout history, followed that same process. They asked questions about certain types of human experiences and perceptions (usually numinous and liminal experiences, those experiences not attributable to normal senses and sensibilities) and performed experiments (developed practices, which they repeated over time). We now know that mystics throughout time and across cultures arrived independently at the same “truths”: there is an energetic realm that interpenetrates the purely physical, material realm; this world can be perceived, these energies can be experienced and in some forms communicated with; there is a human spirit that is independent of mind and body but that can be experienced through the mind and body; and other such ideas, which have come to be called the “perennial truths.” The mystics from various cultures, throughout history, may have had little or no contact with or knowledge of each other, but they provided us a series of maps (each created through their particular mystical approach and practice), and the features, topographies, landmarks of each map turn out to be strikingly similar. Because of the similarities, we can overlay these maps and create one, cohesive master map. So mystics were like scientists who have each independently verified the universal features of the mystical realm.

What exactly are the core principles of Andean mysticism? And what first attracted you to it?

Let me say that the Andeans don’t call themselves mystics. The Quechua word for a practitioner of the ancient ways is a paqo, which more or less means healer. Outsiders, people from the US and Europe especially, who talk about the tradition use words like Andean shamanism and Andean mysticism. Of the two, I think mysticism is closest to the way Andeans conceive of the living universe and practice interacting with it. It is not shamanism, using the traditional or academic definition of that term. My primary teacher, Juan Nuñez del Prado, prefers to call the tradition the Andean “spiritual arts” and he generally doesn’t use either the word shamanism or mysticism.

I had studied and/or practiced in various traditions, and I grew and evolved as a human being in beneficial ways as a result of each of the offerings of these various approaches. But when I found the Andean tradition, through my primary teacher Juan, I was struck by how it was in agreement with core features of science, including modern science. I was struck by its simplicity and elegance. I like to use the metaphor, the cartoon really, of a physicist who is searching for a law of nature and has an entire wall of whiteboard covered top to bottom and side to side with complex equations. And when that scientist finally uncovers the truth of Nature, a law of Nature, all that math collapses down to a simple equation: e = mc2 or f = ma. The Andean tradition is like that, for me at least. It is the essential, the elegant, the distillation, devoid of thousands of years of philosophy and theology, kept to the core essentials. Maybe that is because the Inca and pre-Incas did not have a written language. It was an oral culture. Only the essential truths could be transmitted orally through time.

How is this relating to science in real life?

I say it is like science, so let me provide an example. It is one of the few, perhaps the only, system that says that the living energy is devoid of moral overaly. There is no good or bad energy. No angelic or demonic energy. No dark, contaminating, evil energy. Just living energy, although that energy can be expressed along a spectrum from the lightest (called sami) to the heaviest (called hucha). Hucha is not evil or harmful. It is only the living energy slowed from its natural state/speed/flow. And only human beings can slow the living energy down, perhaps even block it. Ideally, we want to perfectly absorb life-force energy, let it flow through us, and radiate it out. We want it to flow continuously through us, imparting its well-being, the power and vigor of life. But through our psychology, our tangled emotions, our shadows, we reduce our ability to perfectly absorb the life-force energy. We slow it down or block it. That’s hucha. It can’t hurt us. It’s not evil or threatening. It’s just life-force energy that we have caused to lose some of its transformative power. And so we lose some of our power. We don’t function as well and we reduce our ability to grow and evolve.

So the good old-fashioned Western idea of morality does not come into this?

The Andean path is a path of conscious evolution, both of individual human beings and the entire collective human species, and hucha makes our progress much more difficult and slow. But in terms of energy, it is not about morality. The Andeans accept no moral overlay onto the universal energy. In science it’s the same: energy is just energy, without moral overlay. There are no angelic photons or demonic electrons. There are no contaminating, hurtful, threatening protons. In a similar way, for Andeans, there is only the living energy, in its countless configurations in the material world. Only humans can slow the flow of that energy and the worst that happens is it becomes “heavy” and we feel that heaviness. But there is nothing to fear. That said, as social creatures living in communities, we have to choose a moral or ethical system so we can live together. But that is cultural, and is not projected onto energy according to the Andean mystics.

An Andean paqo, thus, wants to be a master of the world of living energy, able to perceive and work with every configuration of energy. They tell us there is nothing you have to protect yourself from or fear in relation to the living energy. A human being may be threatening or evil, due to culture, psychology, emotions, and so on. But in terms of the universal living energy—it is just energy and beyond moral labels.. The universe is a field of living energy in which we can all freely play. In fact, the word most closely associated with the Andean mystical work is pukllay, play. It’s a path of joy.

You have been to Peru quite a lot. What was happening there?

I have lost count how many times! I think I have been about ten or eleven times. Sometimes for my own work and in recent years taking groups of my students. Of course, Peru has changed since I first went there in 1994. Cuzco now is a thriving city that has been largely “Westernized.” The paqos—practitioners of the Andean sacred arts—are no longer only farmers and herders. The people I most had contact with are the Q’ero, and they now come to the city all the time and they are becoming modernized. Thankfully, the young people are now almost all in school, and everyone has access to items that make their lives easier and healthier, from pots and pans to more nutritiously varied foods to soap to medicines. More and more people have cell phones. More homes or villages have solar power or electricity. Where their lives were isolated and difficult in many ways, they are now much easier and more connected with the outside world on a global scale. They love that! They want what we all want: a fuller human experience; an easier, physically healthier, intellectually more varied, and overall more connected life. Yet most of them still retain the knowledge and practices that have been historically valued, including the traditional spiritual practices. So, like all cultures, theirs is changing, both for good and for ill. But from my limited knowledge, mostly for the good.

Andean Qero Pacos

How much of it is still a living, genuine native culture?

When I first went there many, maybe most, of the young people from Q’ero wanted to move down to the cities and towns. Life was, in some respects still is, very difficult high in the mountains. They wanted education, to earn a living, to know the larger world and all its marvels. Eventually, almost ironically, when “outsiders” like me started to seek out their paqos and study their tradition, they began to reconsider the value of their ancient ways and knowledge. It was like they said to themselves, “If these people from other places are coming here to know about the ways of my father and grandfather, maybe there is something I should pay attention to also.” So our interest, in some measure, sparked interest in the young people, who like so many young people reject their parents’ ways. They decided to take another look. Many ended up staying, or returning to their villages, to learn these ways and preserve them. Many of the young people I met in the mid 1990s, who were in their 20s then, are now some of the most respected paqos in their communities.

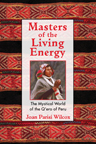

Joan’s Book Masters of the Living Energy

Tell us about your first book, which is about the Q’ero paqos. How did that come about?

When I first started studying the tradition there were very few people in the United States who taught it. Who even knew of it! And what information was starting to be available was of questionable authenticity and accuracy. I didn’t know that until I first went to Peru and experienced the disconnect between what I had heard about it or read about it and what I actually found there. So a few years later, after I had met Juan Nuñez del Prado, who is an anthropologist, I asked him to help me set up interviews with the paqos. My intention was to get information directly from the paqos and so not have to rely on secondhand sources. Juan’s father was also an anthropologist and was the leader of the first modern expedition in 1955 to the Q’ero, the people who are considered by everyone, from the government to the academics, to have most purely preserved the ancient knowledge. I wanted to hear from the paqos themselves, and Juan was instrumental in my being able to do that.

How did you do this?

In 1996 I rented a hacienda where six Q’ero paqos would meet with me, Juan, and the Quechua and Spanish translators I had hired to sit for interviews. It was not easy! They are not used to being interviewed. They are not philosophers, and were paqos of few words. It was difficult to go through three languages: Quechua to Spanish to English. It took hours and hours, and deep concentration on everyone’s part. But once we all got in the groove, it went well. We spent eight to ten hours a day for nearly a week talking, with me recording everything. I let them speak for themselves, and I got a window into their worldview and practices. It was an amazing experience, and I tried to preserve the flavor of that situation in my book. I let the paqos speak for themselves, without a lot of commentary and interpretation. In fact, I purposely included my own process—my own confusion at times, frustrations, and so on—so readers could vicariously to be there with me, looking over my shoulder and listening.

This later became a book?

Yes. The first version of that book was called Keepers of the Ancient Knowledge. I updated the book with more material years later when it came out in paperback under a new title and different publisher, as Masters of the Living Energy. That book has been in print for over twenty years, and readers have told me they call it the Bible of Andean mysticism. I am proud of it, mostly of having preserved these older paqos’ words. Most of them died within a decade of our interviews. They are gone. But they live on in Masters of the Living Energy. They imparted knowledge that the younger paqos today don’t know or weren’t taught, but which we now have.

I stay humble though. I have to say that in the last decade or more I have continued to study, learn, and practice, and I know so much more today than I did when I wrote that book. Because of my increased knowledge and deepened practice, I know there are errors in Masters of the Living Energy. But mostly it is a reliable guide to the core Andean concepts and practices.

Is there another book on the way?

Yes, I am working, slowly, on a new book. Its working title is Andean Energy Dynamics: Practicing Andean Mysticism for Personal Growth. It’s about using the Andean practices and its cosmovision in our Westernized cultures, in our modern lives, to live with greater well-being and to fertilize our personal evolution. It’s not trying to present the whole tradition, but focuses instead only on those concepts and practices that are especially powerful for quickening our growth, fostering our personal evolution of consciousness.

What is the structure of the Andean worldview?

The Andeans identify seven levels of human consciousness. Most of the world is at the third level, with some at the fourth. But we are capable of reaching the seventh level in human life, in this lifetime. The seventh level is where we are Taytanchis ranti, equivalent to God. The sixth level is enlightenment. But the seventh level is God in the human and the human as God. We are capable of that. And the Andean tradition and its practices are all about helping us reach it—or at least aspire to it. We don’t think small! This path is all about flowering the self: being the most glorious human being possible. And through practicing this tradition and teaching it, I can attest that these simple practices can change lives.

Macchu Pichu

Interestingly there are some similarities between Andean, Hopi and Mayan prophecies particularly relating to what Westerners would call the Age of Aquarius, Hindus call the end of Kali Yuga and Mayans refer to as the ‘end of time’. What are we talking about here when it comes to Andean culture? When is this happening?

There is an Andean prophecy about a period of time during which human beings can accelerate their growth, as individuals and as a species. It’s a prophecy of the Runakay Mosoq, the rise of the New Humanity. We are in the midst of this auspicious period, which is considered a time of cosmic transmutation. But our evolution is not a guarantee. We have to do the work. This is a path of personal responsibility. In each class, which I now have to teach only online, I am teaching so many people who are ripe for their own transformation, just an amazing group of people. The quality of people being drawn to this practice is so different from what it was twenty years ago in terms of their being grounded and responsible. In terms of not flitting about from one New Age course to another, but focusing in on work that takes them deep into themselves and living it, day after day, sometimes moment by moment in the seeming chaos of the world. People are so ripe for transformation now. It’s palpable! Andean prophecies are not passive stories. They are active. Paqos are actively working them. And now so are people from all over the world.

BW: Thank you Joan! It was so good talking to you. We are looking forward to this book.

By Billie Krstovic

About Joan Parisi Wilcox

Joan Parisi Wilcox, a teacher of Andean mysticism, is the author of three books and dozens of articles, and has been interviewed on radio and part of many documentary films. Joan’s blog about Andean mysticism is “House of the Hummingbird” at

www.QentiWasi.com.