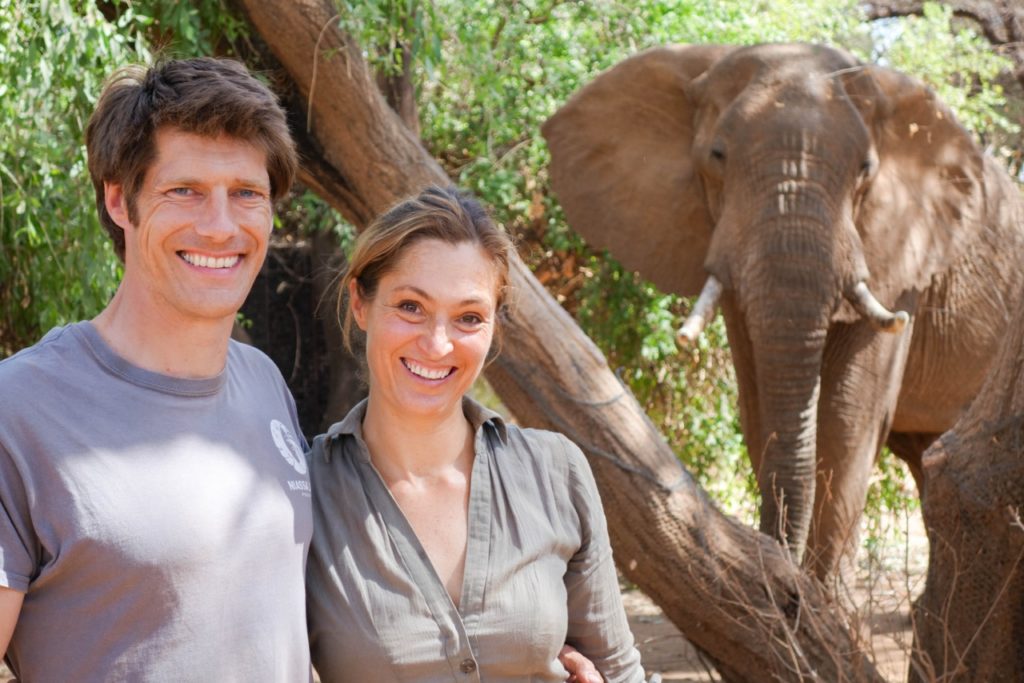

Incredible woman, mum, conservationist and activist, Saba Douglas-Hamilton speaks to Berkshire Woman about her work, elephant poachers and her life in remote Africa. In the true style of a Superwoman Saba’s powerful words speak for themselves. If you are not going to see her live in April on her tour A Life With Elephants this interview is the next best thing!

Photo by Sam Gracey

I really wish Saba would write a book, her words are so powerful. A knowledge junkie, I am weighing my own words carefully as I want her to tell me everything she feels is important about her work. She surprises me with every answer she gives me. She is eloquent, deep, well informed and fierce, in an elegant sort of way. She knows her stuff and processes everything with attention. The more I hear her views the more I like her. Her story is of a wild woman, woman of nature, perhaps one we all forget is in us.

BW: Saba, before we ask about you amazing new adventure please tell us first about your background. You grew up in Africa. Please tell us a bit about this first. Who was Saba as a little girl and a young woman growing up with elephants?

SDH: I was born in Kenya, but spent my early life in Manyara National Park, Tanzania, where my father was doing his pioneering research on the social behaviour of wild African elephants. We lived in a series of small rondavels on the banks of the Ndala river, at the foot of a forested escarpment with a waterfall cascading down the cliffs about 100 metres from Camp. I remember splashing in rock pools close to elephants drinking in the river, and bumping into buffalo as we made our way back to our rooms at night. There was a magical place called the Ground Water Forest into which the elephants would disappear for long periods, where natural springs from the Ngorongoro mountain catchment gushed out of the rocks – we’d often stop there to pick fresh watercress in a stream at the end of a day, or climb into the vines wishing we could get higher like the monkeys. We had two little orphaned genet cats and a banded mongoose as pets that my mother had raised by hand, which I think were probably the first great loves of my life.

Image by Rowan Musgrawe-CAR

When my father got his DPhil from Oxford, our family moved back to Kenya where my parents began their fifteen-year campaign to bring an end to the elephant poaching. Ivory trade was legal but starting to spiral out of control. My dad saw the writing on the wall long before anyone else as he lived so close to elephants, but the trade was so entrenched and lucrative that nobody wanted to believe him. So he had to get hard data on the table fast to prove that elephants could simply not sustain the ivory off-take. For a while we relocated to Uganda, shortly after the dictator Idi Amin had been deposed, where my father was made warden of several national parks, trying to protect the last remnant populations of elephants. The country had been torn to pieces by civil war, and when we passed through Kampala there was strict curfew in the Capital at dusk and gunfire almost every night. Even out in Murchison Falls national park, where we spent most of our time, one could hear government troops fighting rebels just across the Nile. Seeing the suffering of the people near starvation, and hearing the stories of what had happened under Amin, left an indelible impression on me.

As a child you cannot help but absorb the physical, intellectual and emotional environment around you, and for me that was always in Africa. Being brought up among elephants meant that both my sister and I thought of them as part of our extended family, and the names of long dead matriarchs from Manyara still hold such resonance in my heart, like the gentle one-tusker Virgo, the formidable Boadicea or enigmatic Ariadne. The few toys we had were elephants, all the painting on the walls of our house were elephants, and their conservation was the main focus of everything we did. So working to protect wildlife has been a calling from the very beginning. Although my sister and I took different career paths, each of us continues to do our bit for elephants. We have been brought up to think and act like conservationists, but just like any parent, we want to leave the world a better place for our children. To me that means fighting for the environment.

BW: What about meeting with friends and family? Apart from the elephants does anyone else visits?

SDH: Both family and friends come to visit every now and then. We’re used to a long-distant social life in Kenya as everyone lives miles apart, so you tend to stay overnight if you go to visit someone. That being said our lives are full of social interaction in Samburu, with many people coming through Camp both from abroad and from the local nomadic communities.

Image by Tim Beddow

BW: How are your girls managing all this? They are so cute but obviously we presume very hardy. Even the food shopping looks hard going. As a professional and a mum this got to be quite difficult to manage. It makes our Saturday supermarket isle dodging look like a jungle adventure of a very different type. I am never complaining again!

SDH: The day I realised my children had adapted to life in the bush was when their baby soft feet, the toes I’d wiggled so often and soles kissed, suddenly developed a raspy quality, a bit like sandpaper, from walking everywhere barefoot. I remember holding one of their little feet in my hand feeling such nostalgia for lost babyhood. Now, instead of howling at a thorn, they simply scuffed their feet in the sand and walked on. It made me feel very proud but also somehow less useful.

In general, the children have taken our stripped-down lifestyle in their stride, learning how to make bows and arrows with the warriors and sliding easily between English and Kiswahili in conversation. Although we employ a Samburu warrior (we call him our Ninja-Manny) to keep them out of trouble, I do love the fact that one must be mindful – every minute – of the proximity of large predators. In fact all this last week, I’ve heard leopard calling throughout the night. Hyena too, right next to our tent. The kids have had to learn to identify all nine different scorpion species (using their proper Latin names) out of necessity. It’s hilarious to hear them say, “Mama! there’s a Hottentota trilineatus in the bathroom”. Their interest thrills me to bits, but scorpions can be lethal for children, so that’s the one area we have to be extremely careful about safety

BW: Is there any particular educational resource you would advise to parents for their children about conservation?

SDH: Well firstly, I would urge parents (all adults in fact) to see a film called Racing Extinction. It’s a few years old but it’s a good place to start. Then I’d encourage these same grown-ups to read Half Earth: Our Planet’s Fight for Life by E.O. Wilson. With these under their belt, they’ll be in a great place to start thinking about how to explain the situation to their kids. In my opinion, our understanding of our place in the world needs to be firmly grounded in Science, especially biology. I am often astounded by the disconnect in people’s minds between their day to day life and our absolute reliance on the natural world. Unfortunately we seem increasingly trapped in a culture of rogue materialism that is bankrupting our planet. We simply cannot continue with the business as usual model when it comes to consumption. There also needs to be much more accountability and transparency in how things are procured and produced, their long term environmental impact and pollution. I’ve often felt that too many academic disciplines – especially at tertiary level – are taught in isolation, and Economics is a prime example. So broadening the education system to prioritise environment is critical. In the end, there is one overriding cause that unites us all, the health of our biosphere which underpins the very fabric of life on which we all depend for our survival. We live on a finite planet, a fact that we ignore at our peril. Turning things around should be our number one priority.

Image by Frank Pope

BW: Is there anything we can do as consumers to help?

SDH: YES! We all need to cut our consumption and be much more aware of where things come from and the impact this has on the natural world. One should NEVER buy wildlife products. One must always check the labels for things like palm oil (in all its hidden forms), stay informed and help where one can by joining hands with effective conservation organisations.

BW: You are due to arrive to the UK soon. How often do you come over? Tell us a bit more about your upcoming UK tour, what are you trying to achieve with it and what can people expect when they come to see it.

SDH: I try not to take international flights too often, as I am increasingly conscious of my carbon footprint. But if there’s a very good reason, especially if it’s linked to conservation, then I make the most of it. What’s inspired me to do this tour is knowing that so many people across the world have a great love for Africa, or for wildlife, and want to do something to help. So I’d like to reach out to them. I love Obama’s comment “we are the change we seek” and I truly believe that by joining hands we can make a difference.

Part of my talk will be about the early days in Tanzania where my father was getting to know Boadicea, Ariadne and other ferocious females, both human and elephant. Then, a bit about our years in Uganda fighting to save elephants just after the dictator, Idi Amin, was deposed. I’ve got some lovely film clips to illustrate my decade with the BBC natural history unit, filming rare or endangered wildlife in remote places, and also of the key moments that changed the course of my life and brought me back to conservation. Of course, there’s a lot about the work we’re doing now to conserve elephants in north Kenya, studying the minds of these fascinating giants and their intense social relationships, as well as my current passion working with eco-warriors from the local communities to catalyse a grass root environmental movement. Oh, and there’s a bit about my kids too, growing up as Wildlings under the tutelage of several Samburu warriors!

Image by Tim Beddow

BW: Now the dreaded poacher question. How bad is it?

SDH: Adult elephants don’t have much to fear in the natural world beyond an occasional powerful alliance of lions. But they do have everything to fear from people. The destruction caused to Africa’s elephants by the ivory trade boils down to human greed and desire. Elephants are still being killed at an unsustainable rate for their ivory, which is moving illegally across Africa and into Asia at an undiminished rate.

We’ve recently had bad news from Botswana, which holds Africa’s largest elephant population of an estimated 130,000 elephants. The wave of poaching that swept across central and east Africa started to hit southern Africa a few years ago and we’re now seeing an increase in poaching both in Botswana and in Kruger National Park in South Africa. So far it’s not enough to have a big impact on the total population there but numbers in themselves are no defence when poaching picks up. Tanzania had Africa’s second-largest elephant population but lost 60% of it in just five years when things got out of control. Although last year began with positive news of the final closure of ivory markets in China and the decision to close them in Vietnam and Hong Kong over a two and five-year period respectively, there is still a disturbing amount of ivory being seized at borders. Of course that’s also a reflection of increased enforcement, but the amount of ivory still bleeding out of Africa is alarming.

The high price of ivory in China has been the ultimate driver of the poaching of elephants in Africa. After the Chinese government announced that they would be banning the ivory trade within their borders the price fell from over $2,000 a kilo to just over $700 a kilo. While there are other factors – like the state of the Chinese economy – this is good news for elephants. Together with work being done across the continent to train and equip rangers, reform legal processes and take down organised crime networks behind the smuggling of ivory, we’ve seen great progress made in some key areas like Kenya, and even some tough areas in DRC like Garamba National Park. But plenty of challenges remain – the desert elephants of Mali are hanging on by a thread in the midst of an Islamicist uprising, and the last remaining stronghold of forest elephants in Gabon is under siege. So, while great strides have been made, the ivory crisis is far from over. There’s a lot we can do as NGO’s, but regime change can flip things around overnight. In Botswana, the new government has decided to take a populist political line and is suddenly talking about culling elephants and turning them into pet food! Unconscionable.

The other big challenge elephants face is fragmented landscapes with vastly diminished natural habitat and direct competition with humans for common resources. Elephants will only be able to thrive in an increasingly crowded continent if we can convince the people that live alongside them to give them the space they need to survive. That means opening peoples’ eyes to the complexity of elephant consciousness and their intrinsic right to exist, explaining the science of how elephants create ecosystems and hold them together, and showing the people ways to overcome the challenges that living with elephants sometimes present.

The increasing global human population is driving species loss across the planet. Elephants need a lot of space in which to live, but in Africa that space is shrinking, fast. Currently there are around 1.3 billion people on the continent; by the end of the century this is projected to have increased to over 4 billion. Africa’s economies are developing fast, with agriculture on the rise and huge infrastructure projects being put together that threaten to slice up the remaining refuges for nature. Africa’s people urgently need a brighter future but we also need to maintain the connectivity of wild ecosystems. With the kind of data that Save the Elephants (STE) is collecting on how elephants live, where they go, and what they need to survive, we can help guide the planning process so that elephants can continue to thrive even in a human-modified landscape. STE is engaging at all levels, working with the top echelons of government all the way through to the communities on the ground.

My chief interest in this field is how to preserve the integrity of the habitat, which is under siege from every angle. It means working from a grass roots perspective, joining hands, initiating dialogue across different cultures, sharing information so that we’re all on the same page to catalyse change.

BW: If there was a one thing you consider urgent to campaign about on the planet what it would be?

SDH: Human population is a hot potato that few governments want to address. We’ve increased from about 1 billion in 1800 to more than 7.7 billion today. As the human footprint increases so does our rate of consumption, which is now almost pathological in its intensity. Both need to be addressed urgently. I’ve been much inspired by the Half Earth movement – that we must strive to set at least half of our planet aside entirely for nature, to maintain an optimal environment for the future. I would advise everyone to read up on it and get involved.

BW: Obviously your conservation work came out of your upbringing. There are so many things you are involved with from your TV work to conservation. What is the long term aim of your overall work?

SDH: Most of what I do feeds into serving the environmental cause. When I hear frogs croaking and burbling around me, it’s as if a happy clock gets reset inside. Because amphibians are such vulnerable creatures – symbolic of the natural world under siege from every quarter by pollution, disease, climate change, and shrinking habitat – if they’re still singing, like canaries in a coal mine, then it feels like we’re still ok. My long term aim is to share the sense of wonder and curiosity I have for Nature with the outside world – be it a solifuge scuttling about its late night business, or the intelligent compassion of an elephant – exciting people to get involved in healing what has been broken. The interconnectivity of lifeforms in our biosphere is the fabric of life on which we depend for our survival, so it has to be championed above all else.

BW: Now, we are very impressed and intrigued with your latest adventure. In short, you and your young family are off living in the remote place in the middle of nowhere in Africa. Many of our readers are mothers and will find your current adventure incredible . Please tell us who thought of this and what is going on?

SDH: After my second pregnancy, which turned out to be twins, I went over a waterfall of baby care and didn’t resurface to catch breath for two years. But when I did, a surge of longing for wild places hit me like a steam train and I knew I had to get out of suburbia (Nairobi) before I lost my (milk-producing) mind. Thankfully, the stars aligned at the right time – we were in need of someone to take over the running of Elephant Watch Camp, and all hands at Save the Elephants were on deck with the ivory crisis which meant that Frank was spending much more time in Samburu. It made a lot of sense to relocate our lives to north Kenya, which is where we have been ever since.

Image by Sam Gracey

BW: Tell us about elephant families. The stories of caring matriarchal figures are most remarkable. It seems their society is much like ours just more nurturing. Is this true?

SDH: Elephants are special because they’re so like humans in so many ways, yet also utterly different. They feel things very deeply, just like us – love, grief, anger, lust – and even much more complex emotions like empathy and compassion that, as far as we know, are shared only by cetaceans and great apes. They’re super-intelligent too, so when one meets elephants one senses an immediate mutual recognition of a parallel consciousness. As highly social animals they are always doing something interesting, and the more you get to know them as individuals, the more you understand that each one has its own unique personality and character, is defined by its life experiences, and relies heavily on the elephants it knows for love and support. All of which is very similar to humans. So the longer we know them, over the years, the more they feel like old friends.

BW: I was hoping you will tell me you are writing a book, or an elephant guide or something like that, something we can use to teach children about this issue, but perhaps there is no time? Any plans for the future at least?

Gestating a book is like waiting for a Camembert to mature. There’s definitely something large and unwritten inside me, but the ooze hasn’t started yet. Like any busy mum, I struggle to set enough quiet time aside in the day to focus. Even finding time to answer your questions has been a challenge! On top of mothering and a full time job, life in north Kenya can be somewhat left field and unpredictable. We’ve chosen an unusual route out of principle, and so unusual stuff happens on a daily basis. I think it will make for some good stories. So, yes, there’s a book coming, that I can confirm 100%.

BW: Saba tell us a bit about your work for TV. The programmes we saw also cover cats, large ones at that. Please tell us how did you get involved with TV, how did your professional journey start?

SDH: I ended up working in wildlife TV quite by chance, by being in the right place at the right time. The BBC were interested in doing a story on my father’s elephant research, and I was his Chief of Operations at the time. When we met the producers in Bristol, one of them was a talent scout who decided to try me out. We made a sweet little film called “Living with Elephants” and all of a sudden I became a wildlife presenter. It was perfect timing as I had become rather demoralised working in conservation. A case of winning some battles but in general losing the war. Having the chance to tell stories that might inspire people to fall in love with the wild world, and getting to see what was happening on the conservation front in other places, was an opportunity for me to use my creative skills and also make a difference. It greatly expanded my horizons and I loved every minute.

But when I started a family things had to change as I couldn’t travel so much anymore. Besides which my priorities altered (no surprises there!), bringing hands-on conservation back into sharp focus. While I knew that making wildlife films was helping win hearts and minds, I wanted to do much more in situ in Kenya. Taking over Elephant Watch Camp was an opportunity to use my abilities as a communicator to open up the world of elephants both to people from outside Africa but more importantly to the people living closest to wildlife. I believe that change begins at home, so where better to start than Samburu where we had already been based for 20 years.

Image by Mirella Ricciardi

What I love best about our eco-camp – Elephant Watch – is the minimal impact it has on the environment. It was designed and built by my mother, Oria, who wanted to create a beautiful place where people could come to learn about elephants. Each tent is built to fit the shape and needs of the tree under which it has been erected, along the banks of a slow-flowing brown river called the Ewaso Nyiro. It’s truly one of the most beautiful places I know. In the morning one is serenaded by birds while hearing the secret rustlings of wild animals awakening all around.

In general, our policy is to go beyond zero impact to positive impact when it comes to sustainability. This is particularly evident in our relationship with the local nomads. And that’s what makes the camp really special – living and working shoulder to shoulder with the Samburu nomads. We employ 96% of our staff from the immediate communities that live directly around the Reserves, which gives us an intimate insight and informed perspective on their world. They are exceptionally brave, stoic people, who follow the rains with their livestock over vast semi-arid landscapes. Talking to them one is often humbled by the hardships they face day to day, yet their wicked sense of humour is never far from the surface. Our aim is to enchant our guests with all things African and elephant, in the hope of winning people over to the conservation cause and growing the constituency that votes in favour of nature.

With the Save the Elephants research centre half an hour downstream, we have unparalleled access to the 20 + year study of Samburu’s 1000 or so elephants that use the reserves as part of their range. Their characters, families, hormones, migration routes, likes and dislikes are all plotted, analysed and assessed, giving us a fascinating glimpse into the secrets of elephant society. We introduce our guests to the many individuals we know well, like Cleopatra and Anastasia from the Royals, Cinnamon from the Spices, or Euphrates from the Rivers families, and knowing each elephant’s triumphs and tragedies, we can explain how each individual chooses to negotiate the trials of life.

In fact, we know the elephants so well that many feel like an extension of our Samburu family. Bull elephants wander through Camp at all times of day and night, and in the sagaram season (when juicy seed pods fall from the Acacia tortillis trees) they live with us almost permanently. It makes for some interesting detours when you’re trying to get back to your tent at night. I was once held hostage for 6 hours in the Mess tent by three bulls who wouldn’t let me leave.

We know each one by the patterns of its ears and shape of the tusks, so they become like old if somewhat belligerent friends. Sarara, the biggest and boldest, often comes to scrape seedpods off the roof of our hut. He is so used to being in Camp that he’s become extremely proprietal, and puts us in our place if he things we’re getting out of line. Only a week ago, I stepped out of my room having not clocked that he was around, and next thing I knew the bushes to my left exploded and he came at me in full charge! For a moment I wondered if I would actually get away from him in time, legging it as fast as i could with my laptop tucked under my arm! Other bulls like to lie down on the banks of the sandy paths and fall fast asleep right next to our tents. We’ve had a pack of wild dog and even lions coming through Camp, and leopards are a common feature. Our kids have learnt by necessity to be bush-wise, keep their eyes open for elephants, snakes and scorpions, and look twice if they sense anything unusual. I’m quite proud of how savvy they’ve become, helped by some of the young warriors who are their mentors. Allowing them this time to open their eyes and hearts to the wild world is the greatest gift we can give them.

BW: Obviously you are in the middle of this unique project. Is there anything else we should watch out for in the future? Any shows, programmes, episodes?

SDH: Not immediately.

BW: Saba one piece of advice or a message for our readers please, something very you!

Image by Frank Pope

I am a great believer in the power of the individual to make change, and this applies as much to how we travel or spend our money as to the way we bring up our children. After all, one can only lead by example. In my view, this means always asking the best of oneself – standing by one’s principles, speaking up when others are silent, or reining in one’s sense of entitlement. So I’d ask everyone to start taking small steps, every day, that favour the environment. Join hands with us. Together, we become a powerful force for change.

BW : We wish you all the best with your project and will be paying attention to how it unfolds. Thank you Saba. Our readers are going to love this!

If you wish to see Saba live this year in the UK she is coming in April for her Tour A Life With Elephants . To book tickets go here:

http://www.josarsby.com/news/2018/11/2/saba-douglas-hamilton-a-life-with-elephants-uk-tour-2019

Interview by Billie Krstovic